GSDA on Diversity and Inclusion

By Meng Wang, GSDA Diversity Chair

The murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Tamir Rice, and many other Black Americans by police have created an implosion of rage and frustration within our nation. It has sparked a call for the dismantling of racist systems that have proven to advantage white people while it actively and intentionally oppresses Black and brown people. The move to fill a Diversity Chair position within GSDA is a long time coming for our organization. Although the need was often recognized, it remains regrettable that one was never ultimately formed until now. This is precisely why our old ways of operating were problematic. We were accustomed to facing challenges in a reactive rather than proactive manner. But we are dismantling those. And we will continue to dismantle, unlearn, learn, and build it back up a little bit better than it was yesterday. At GSDA, we condemn police brutality against the Black, Indigenous, and People of Color in our communities.

There are no words we can say to absolve us of the systemic racism that we have contributed to, knowingly or not. The only thing we can do is to do the work even and especially when no one is looking. It is not the responsibility of our Black and brown acquaintances to educate us or supervise our actions. It is up to each of us to recognize our internal biases, understand our privilege as white and non-Black POC, distribute our wealth and power to purposely work towards dismantling the systems of oppression from its foundation. It may not look perfect but that is the nature of growth; it can be painful. Even though I have the official title, moving forward each and every GSDA board member will be a Diversity Chair in their own way. Every leadership position is tasked with becoming literate in issues surrounding racism with the goal of achieving a diverse and inclusive environment at the forefront of their minds.

The Black Lives Matter movement initially gained momentum as a reaction to police killings, but it quickly exposed the inequities that touch every facet of Black American life. These inequities are a direct result of normalized white supremacy existing as blatant racism, or more often, the acted out in subtle but equally significant forms of racism such as microaggressions, colorism, and misogynoir. We recognize the depth and breadth of problems caused by racism against Black people. As health practitioners, it’s important to acknowledge that racism is just as much, if not more of a public health problem than anything.

Racism is a public health concern.

We have seen how the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affect Black people, where their infection rates are about 5 times higher than white people’s. This is not a new problem but rather a manifestation of a collective pre-existing condition in our country. It is the condition where Black and other darker-skinned minorities (including American Indian/Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders, Hispanics and South Asians) are systematically marginalized when it comes to access, affordability and lack of cultural competency in healthcare.

Black Americans specifically have more than twice the prevalence of diabetes and cardiovascular disease as non-Hispanic whites. When it comes to mental health, Black Americans experience a higher rate of stress-related mental illnesses that can be traced back to the same trauma that slaves endured. In order to better serve our Black and minority communities, we must first become well-versed in the issues they face. Many studies done by experts much smarter than myself are available to better understand racism within our healthcare system, and they will be linked at the end of this post. As we expand our own understanding in this area, we will continue to provide vetted resources related to our field in the Nutrition Resources section.

Racism is a nutrition concern.

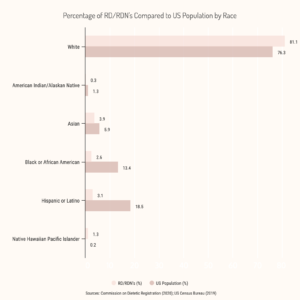

In the dietetics realm, there is a stark lack of diversity among practitioners. A vast majority of dietitians and dietetic technicians are white women. As of June 2020, only 2.6% of dietitians were African American, followed by 3.1% Hispanic and 4% Asian. In addition, 94% were female. This isn’t the only area of healthcare that could see more diversity. Only 5% of doctors are Black; a low number but still twice the number of Black dietitians relatively speaking.

There are various reasons this field lacks diversity, including but not limited an unpaid and competitive internship and low entry-level salaries compared to other medical professions. A study done by the Journal of Critical Dietetics exploring African American views on racism in dietetics details accounts of lack of support in the education system. One participant describes her experience with trying to get help in academia:

“Nobody helped me fill out the forms. I tried to get help but I couldn’t get any. I was in a family with no knowledge of it. Being in that environment [integrated high school], they helped you, but you felt the prejudice. I went there with the other kids, but the administrative staff, they were not as helpful to the African Americans as the other nationalities.”

Another account demonstrates the stigmatization a Black student when she was advised to seek a career in food service or hospitality,

“Do you really want to go into dietetics because it is really, really hard? And I said yes, I’m sure I want to do this. She said do you want to maybe consider hotel and restaurant management which is also in our department. I said no I don’t want to be a hotel or restaurant manager. I want to be a dietitian.”

The underrepresentation of Black Americans and minorities within providers directly influences the ability for these groups to feel seen, heard and understood as patients when it comes to nutrition health. In addition to making nutrition care more accessible on a community level, we have an obligation to start undoing the barriers to entry to this field in all its forms so that dietetics professionals can be an accurate representation of the population they serve. At GSDA, we are committed to doing our part in increasing our work in the community, listening to and supporting Black students who are interested in dietetics, elevating and valuing the voices of Black dietitians, and participating in relevant Action Alerts from the Academy that support diversity and inclusion in our field.

Racism is a food systems concern.

Food is at the heart of the dietetics profession. Structural racism is embedded into the US food system from its origin in growing fields to its final destination in grocery aisles. This problem stems from land ownership, where 97% of farmland is owned and operated by white people while an overwhelming majority of low paying farm worker jobs are held by people of color. The disparity in wealth and control within our farm systems translates to poverty and food insecurity, which then correlates with obesity and other diet-related diseases.

Beyond the racialization of agriculture, there are multiple steps along the supply chain that ultimately create barriers for Black people and other minorities to provide nutritious meals for themselves and their families. The redlining of grocery store locations makes accessing a well-stocked and maintained grocery store an impossible trek for those who live in low-income neighborhoods. Nutrition bloggers and influencers with tens of thousands of followers cater their content to a privileged, mostly white audience who have the means to have fresh fruits and vegetables on hand at all times. As of 2018, 21.2% of Black households experienced both low food security and 9.1% experienced very food security, both of which are double the rate that non-Hispanic white households experienced. If so many lack the income or support to obtain basic needs, our frames of thinking must be attuned to the realities those in our communities face when it comes to talking about food choices to our patients.

As a last word here, I defer to Eric Holt-Giménez, the Executive Director of Food First, who speaks on racism in the food system much better than I ever will:

Calls to “fix a broken food system” assume that the capitalist food system used to work well. This assumption ignores the food system’s long, racialized history of mistreatment of people of color. The food system is unjust and unsustainable but it is not broken—it functions precisely as the capitalist food system has always worked; concentrating power in the hands of a privileged minority and passing off the social and environmental “externalities” disproportionately on to racially stigmatized groups.

The topics I have outlined only glance at the issues related to diversity at large and within dietetics. If we have learned anything from the Black Lives Matter movement, it is that the resources are out there if we go look for them on purpose. As dietetics professionals, we are in a unique position of privilege that can be leveraged to support racial justice in the nutrition and healthcare fields. Follow our private Facebook group and Instagram to stay updated on resources, events and workshops that offer continuing education credit throughout the year supporting Black Lives Matter as well as Black, brown and minority RD’s-to-be and dietitians. Until the food, mental and physical well-being, access to healthcare and lives of Black people matter, all lives do not matter.

Special thanks to Emahlea Jackson for her contributions to this post.

References & Further Reading:

COVID-19 in Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups (2020) https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html

Registered Dietitian (RD) and Registered Dietitian Nutritionist (RDN) by Demographics (2020) https://www.cdrnet.org/registry-statistics-new?id=1779&actionxm=ByDemographics

“Hearing the Voices”: African American Nutrition Educators Speak about Racism in Dietetics (2013)

https://criticaldieteticsblog.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/journal-of-critical-dietetics-p26-35.pdf

Racial, ethnic and gender inequities in farmland ownership and farming in the U.S. (2018) https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10460-018-9883-3#:~:text=In%20terms%20of%20race%2C%2097,%2C%20and%2014%25%20of%20tenants.

Spatial Supermarket Redlining and Neighborhood Vulnerability (2016) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4810442/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CSupermarket%20redlining%E2%80%9D%20is%20a%20term,to%20suburbs%20(Eisenhauer%202001).

Dismantling Racism in the food system (2016) https://foodfirst.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/DR1Final.pdf

Cultural Competence and Ethnic Diversity in Healthcare (2019) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6571328/pdf/gox-7-e2219.pdf

Barriers to Becoming Registered Dietitians Identified by African American Students and Practitioners (2018) https://criticaldieteticsblog.files.wordpress.com/2018/07/41-46-white.pdf

Diet-related Disparities: Understanding the Problem and Accelerating Solutions https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2729116/